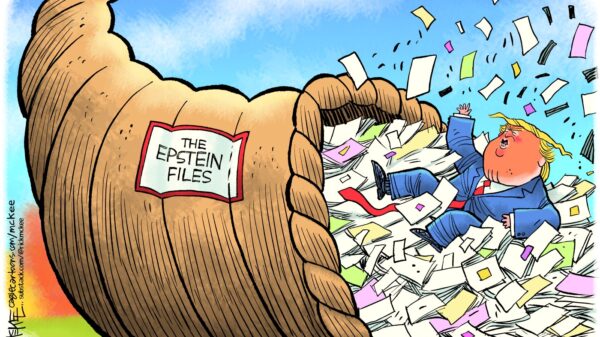

On Monday, the Trump administration presented arguments to the Supreme Court asserting that no court can question the president’s authority to deploy military troops within the United States. Trump’s legal team contends that the decision to call up the National Guard is a fundamental exercise of his power as Commander in Chief, supported by a clear delegation from Congress. They argue that such decisions should not be subject to judicial review, citing the case of Martin v. Mott from 1827, which they misinterpret to bolster their claim.

The administration’s filing specifically references Trump’s deployment of the National Guard in Chicago, citing “violent, organized resistance” against ICE agents. The legal argument implies that this determination falls outside the purview of judicial review, stating it warrants “extremely deferential review” at the very least. The argument draws on historical precedent, but critics note that the original case did not address judicial review, instead focusing on the limits of military authority.

Public sentiment largely opposes military interference in domestic affairs. A significant majority of Americans, regardless of political affiliation, disapprove of deploying military forces in cities without a foreign threat. This resistance can be traced back to the Revolutionary War, where colonists experienced the oppressive presence of British troops, leading to a deep-seated mistrust of a standing army. The U.S. Constitution reflects this concern, granting Congress the authority to call forth the National Guard to “execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions,” thereby limiting the president’s unilateral power.

The legal framework also includes Title 10 USC 12406, which outlines specific conditions under which a president may mobilize the National Guard. Additionally, the Posse Comitatus Act prohibits the use of federal armed forces to enforce laws unless expressly authorized by the Constitution or an Act of Congress. This law underscores a historical reluctance to allow military control over civilian populations.

In their arguments, Trump officials, often supported by media outlets, have portrayed a narrative of extreme violence against ICE personnel, suggesting that agents face persistent threats in Illinois. They allege that ICE agents endure ambushes and attacks from protestors, which are purportedly encouraged by dangerous gangs. However, eyewitness accounts and video evidence frequently contradict these claims. For instance, in reported incidents of ramming, evidence shows that ICE vehicles were often the aggressors.

Both the Ninth and Seventh Circuit Appellate Courts have previously rejected Trump’s assertions that military deployments are beyond judicial scrutiny. These courts emphasized that the statutory text requires specific conditions to be met before a president can deploy the National Guard. The Ninth Circuit’s decision is currently awaiting a full en banc review, while the Seventh Circuit determined that the situation on the ground did not align with ICE’s reported claims. The Supreme Court has since requested supplemental briefs regarding the interpretation of 10 USC 12406(3), which pertains to the president’s authority when regular forces cannot enforce U.S. laws.

The implications of Trump’s belief that his military deployments are immune from court review raise significant concerns. Critics warn that such a stance could escalate tensions and violence against civilians, particularly as he has labeled dissenters as “domestic terrorists.” The outcome of this case could play a crucial role in defining the limits of presidential power in domestic military affairs and the protection of civil liberties.

As the legal arguments unfold, the focus remains on whether the Supreme Court will establish clear parameters for military engagement within U.S. borders, particularly in light of historical precedents and constitutional protections.