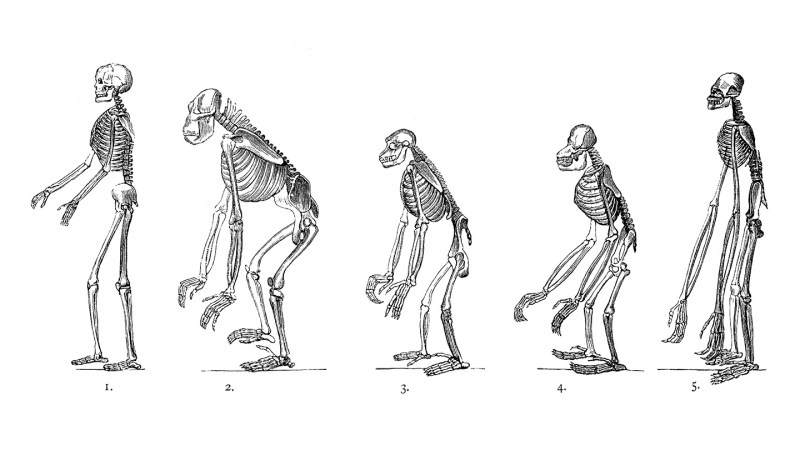

Groundbreaking research has identified two small genetic changes that played a significant role in the evolution of human bipedalism. According to a study published on September 25, 2023, in the journal Nature, these genetic shifts were crucial in reshaping the human pelvis, allowing our early ancestors to walk upright.

The first genetic alteration involved a 90-degree rotation of the ilium, the bone located at the uppermost part of the pelvis. This rotation reoriented the muscles that connect to the pelvis, transitioning the structure from one that supported four-legged movement to one designed for standing and walking on two legs. The second change delayed the hardening of the ilium from soft cartilage into bone, as explained by Gayani Senevirathne, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard University.

Research Insights on Pelvic Evolution

The researchers conducted detailed examinations of developing pelvic tissue from humans, chimpanzees, and mice under a microscope, complemented by CT imaging. They discovered that human ilium cartilage grows sideways rather than vertically, as seen in other primates. This unique growth pattern, along with the delayed transition from cartilage to bone, allows the pelvis to expand laterally, forming a distinctive bowl shape that supports an upright posture.

Co-author Terence Capellini highlighted that these changes were essential for redistributing muscle locations. Muscles that previously aided in forward motion in quadrupeds transitioned to the sides of the pelvis, which is vital for maintaining balance and stability while walking.

The study reveals that the genetic shifts are linked to biological switches that control gene activity. In humans, genes responsible for cartilage formation activate in areas of the growing ilium, promoting horizontal growth. In contrast, genes that facilitate bone formation activate later, allowing enough time for the pelvis to develop its characteristic shape.

Implications for Human Evolution and Health

The findings suggest that these genetic modifications occurred early in the hominid lineage, after humans diverged from chimpanzees. This research supports a central tenet in evolutionary developmental biology: significant anatomical changes often arise from minor adjustments in gene activity rather than the emergence of entirely new genes.

Anthropologist Carol Ward from the University of Missouri emphasized the importance of these adaptations in establishing the ability to walk on two feet, enabling humans to stand on one foot at a time.

Interestingly, the research initially aimed to explore pelvic and knee formation to gain insights into hip disorders. Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the study also uncovered that these evolutionary changes could render human hips more susceptible to conditions like osteoarthritis, which occurs far more frequently in humans than in other primates.

Additionally, Capellini speculated that the wider hips resulting from these changes could have facilitated a larger birth canal, potentially allowing the evolution of larger-brained infants. This connection raises intriguing questions about the interplay between pelvic evolution and brain development in humans.

The implications of this research extend beyond evolutionary biology, as understanding the genetic basis for pelvic development may inform future biomedical studies aimed at addressing hip-related disorders. The intricate relationship between evolution and health continues to be a fascinating area of exploration for scientists and researchers alike.