Recent research has revealed that moonquakes, rather than meteoroid impacts, are responsible for significant changes in the terrain near the Apollo 17 landing site on the Moon. This discovery, made by scientists from the University of Maryland, indicates the presence of an active lunar fault that has been generating seismic activity for millions of years. These findings could have major implications for future lunar missions, particularly regarding the construction of long-term habitats.

Understanding Moonquake Risks

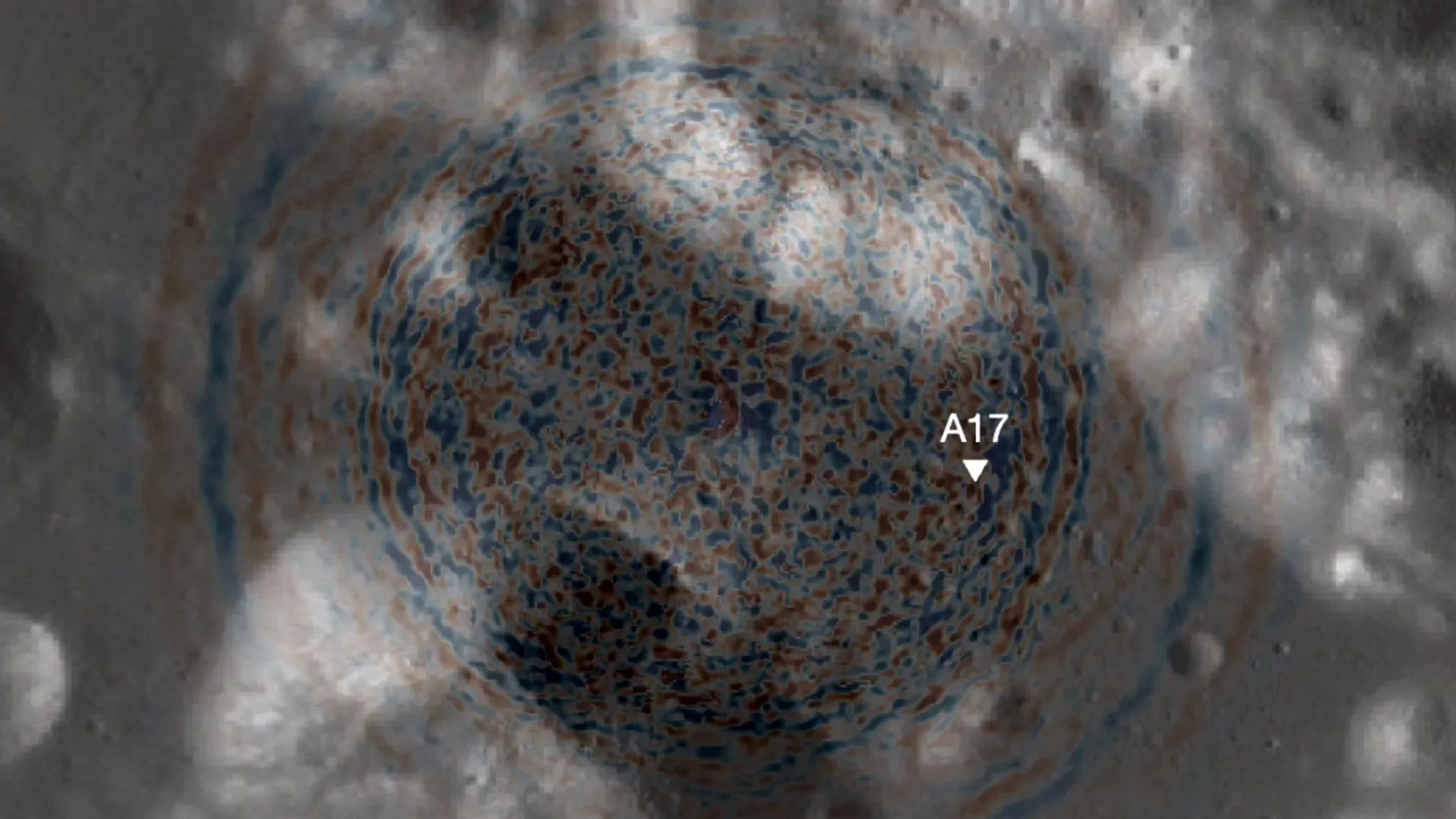

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, highlights the Taurus-Littrow valley, where Apollo 17 astronauts landed in 1972. Using data collected during the mission, researchers identified that moonquakes have been the main factor in shifting the region’s terrain. This is a significant shift from prior assumptions that meteoroid impacts were the primary cause.

Led by Thomas R. Watters, Senior Scientist Emeritus at the Smithsonian Institution, and Nicholas Schmerr, an Associate Professor of Geology at the University of Maryland, the research team examined geological samples and observations. Their analysis included boulder tracks and landslides believed to have been triggered by these seismic events. According to Schmerr, “We had to look for other ways to evaluate how much ground motion there may have been, like boulder falls and landslides that get mobilized by these seismic events.”

The findings suggest that moonquakes, with magnitudes around 3.0, have affected the area over the last 90 million years. The activity is associated with the Lee-Lincoln fault, a tectonic structure that cuts through the valley floor. This raises concerns that the fault remains active and could continue to affect future lunar operations.

Implications for Future Lunar Missions

The study also assessed the risk of damaging quakes occurring near active lunar faults. Researchers estimate a one in 20 million chance of experiencing a significant quake on any given day. While this may seem low, Schmerr emphasizes the need for careful planning: “The risk of something catastrophic happening isn’t zero, and while it’s small, it’s not something you can completely ignore while planning long-term infrastructure on the lunar surface.”

For short missions, such as Apollo 17, the risk is minimal. However, as NASA prepares for the Artemis program, which aims to establish a sustained human presence on the Moon, the risk profile changes dramatically. Projects involving longer stays face a growing hazard, particularly with taller lander designs like the Starship Human Landing System, which may be more vulnerable to ground acceleration from nearby quakes.

Watters and Schmerr’s research indicates that if astronauts were stationed on the Moon for an extended period, the risk of experiencing a hazardous moonquake could increase significantly—potentially to around 1 in 5,500 over a decade of continuous presence. “It’s similar to going from the extremely low odds of winning a lottery to much higher odds of being dealt a four of a kind poker hand,” Schmerr added.

This research is part of a broader field known as lunar paleoseismology, which investigates ancient seismic activity on the Moon. Unlike Earth, where scientists can dig trenches for evidence of past earthquakes, lunar researchers rely on pre-existing data and orbital imaging. Future advancements in mapping technology and the deployment of more sophisticated seismometers during the Artemis missions will likely enhance understanding in this field.

Schmerr urges that future lunar exploration must prioritize safety: “The conclusion we came to is: don’t build right on top of a scarp, or recently active fault. The farther away from a scarp, the lesser the hazard.” The study received support from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission, which has been providing valuable data since its launch on June 18, 2009.

As NASA continues to develop plans for human exploration of the Moon, these findings underscore the importance of assessing geological risks to ensure the safety and success of future missions.