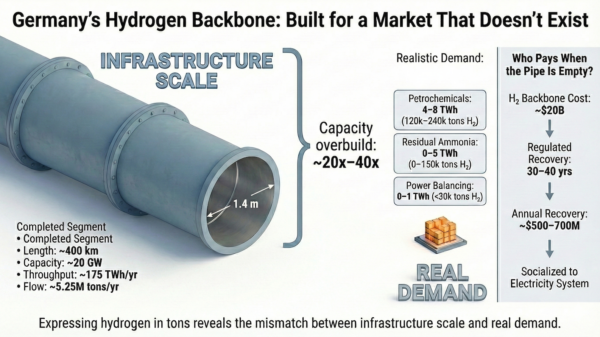

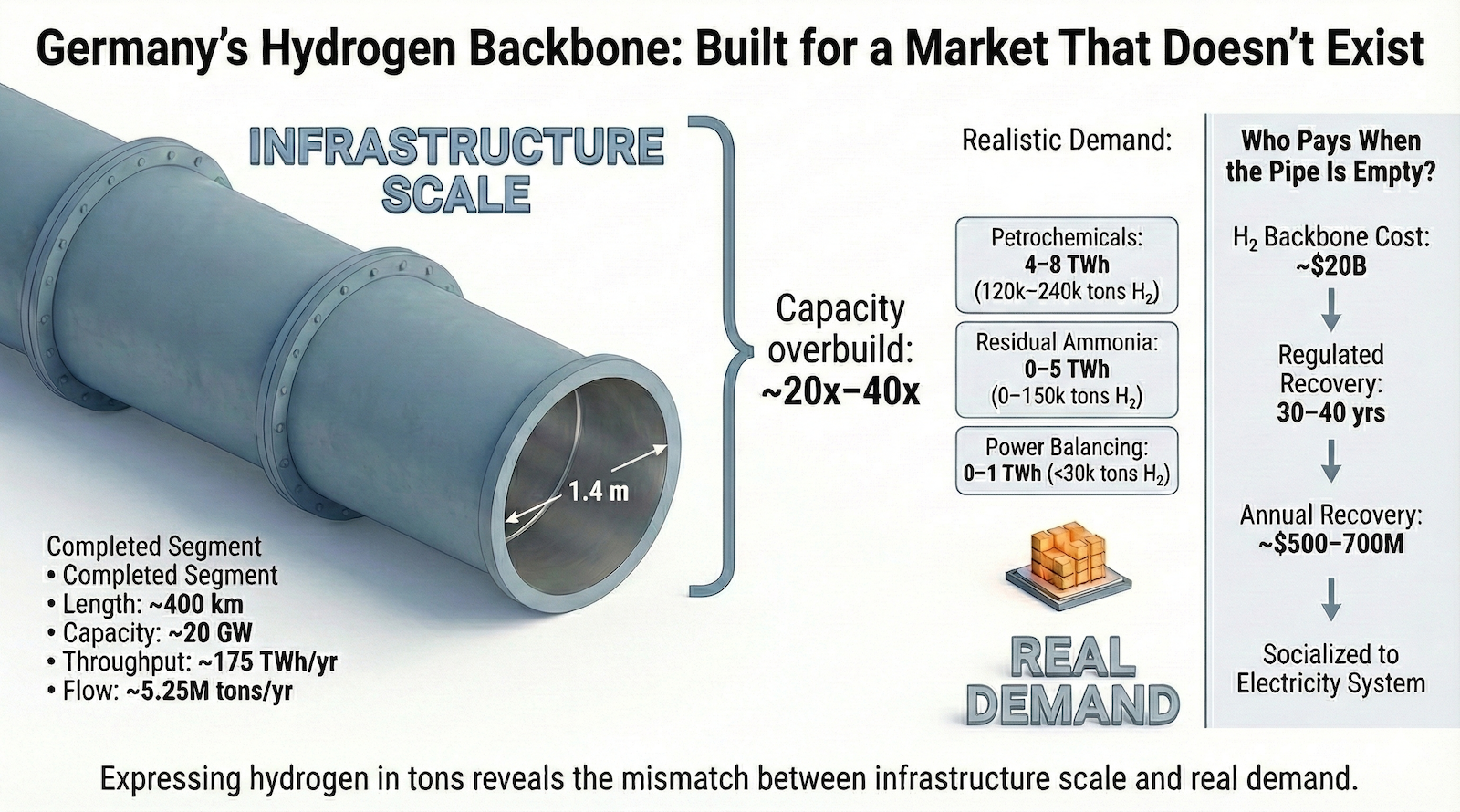

Germany has successfully completed and pressurized a significant segment of its national hydrogen infrastructure, covering approximately 400 kilometers. The system is now technically operational, with the necessary pipes and compressors in place. However, there is a critical issue: the lack of hydrogen suppliers and customers connected to the network. This situation reflects a deeper structural problem in the demand for hydrogen rather than a mere delay in commissioning.

The implications of this disconnect extend beyond hydrogen policy. The substantial costs associated with this infrastructure will not vanish; they will be reflected in higher electricity prices for consumers over the coming decades. The ambitious vision behind the hydrogen backbone was to establish a national transmission network of around 9,000 kilometers, intended to facilitate a transition from natural gas to hydrogen across various sectors, including steel production, chemical manufacturing, and transport fuels.

Understanding the Economic Impact of Hydrogen Infrastructure

In policy documents, projections indicated that hydrogen demand could rise sharply, reaching between 100 TWh and 130 TWh by 2030. This was based on the assumption that hydrogen would serve as a versatile energy carrier. However, the choice of energy units to describe hydrogen demand has often led to misconceptions.

Hydrogen, measured in kilograms and tons, should not be compared directly with electricity measured in TWh. For context, one kilogram of hydrogen contains approximately 33.3 kWh of usable energy. Thus, 1 TWh of hydrogen corresponds to about 30,000 tons of hydrogen. Using TWh to gauge hydrogen demand can create a misleading analogy, implying that hydrogen is as easily transportable as electricity. Such comparisons obscure the complexities of hydrogen production, including the significant energy losses involved in its conversion from electricity to hydrogen and back again.

Germany’s current hydrogen strategy relies on assumptions that do not align with economic and physical realities. The country has high electricity prices, making domestic green hydrogen production less competitive, especially when considering the electricity consumed in the electrolysis process, typically requiring between 50 kWh and 55 kWh of electricity for each kilogram of hydrogen produced. This situation challenges the feasibility of producing hydrogen at the anticipated scales.

The Disconnect Between Infrastructure and Demand

Germany’s hydrogen infrastructure was designed with the expectation of securing robust supply agreements. Ports like Rostock and Wilhelmshaven were earmarked as entry points for hydrogen imports. Yet, many prospective suppliers are opting to ship finished products, such as ammonia or methanol, rather than gaseous hydrogen itself. This disconnect indicates that the anticipated demand for hydrogen has not materialized as expected.

Demand for hydrogen in Germany is currently concentrated in oil refining, which consumes between 25 TWh and 30 TWh of hydrogen annually. However, as Germany shifts towards decarbonization, this demand is likely to decline significantly. The hydrogen required for petrochemical processes is also much lower than previously assumed, with estimates suggesting an annual need of only 4 TWh to 8 TWh of hydrogen once fossil fuel refining phases out.

This reevaluation leads to a stark contrast between the designed capacity of the hydrogen backbone and actual demand. The commissioned 400-kilometer segment is designed to handle around 20 GW of capacity, equating to approximately 175 TWh per year, while realistic demand may only be between 4 TWh and 14 TWh. This creates an overcapacity of approximately 22x to 44x.

The financial ramifications of this disconnect are profound. The estimated cost to construct the hydrogen network is around $20 billion, with annual recovery costs projected between $500 million and $700 million. This will inevitably lead to increased electricity prices for consumers as the costs are spread across the wider energy system.

Germany must consider whether to continue expanding this hydrogen backbone or to pivot towards more practical solutions that align with its energy transition goals. Investing in traditional energy infrastructure, such as grid reinforcement and renewable energy sources, could yield better economic outcomes and support the necessary decarbonization efforts.

In summary, while Germany’s vision for a hydrogen economy is commendable, the mismatch between infrastructure development and actual market demand poses significant risks for consumers and the broader energy transition. The country faces a crucial decision: redirect funds towards viable energy solutions or continue investing in an underutilized hydrogen network that may not deliver the promised benefits.