Connecticut schools are experiencing significant changes this fiscal year as the state government commits nearly $2.5 billion to local education through the Education Cost Sharing (ECS) grant. This funding, which constitutes over 10% of the General Fund, aims to enhance educational equity across the state’s districts. However, critics argue that the funding formula has failed to keep pace with inflation, exacerbating funding disparities between affluent and less wealthy communities.

Understanding the ECS Funding Formula

The ECS formula operates on a “foundation” level that estimates it costs approximately $11,525 to educate each student in Connecticut. This figure is adjusted based on various factors, including the number of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals and those who speak English as a second language. Additionally, the formula evaluates the wealth of a district by considering both property values and resident income.

Historically, Connecticut relied heavily on local property taxes to fund K-12 education, which led to stark contrasts between rich and poor regions. The situation prompted the Connecticut Supreme Court to intervene in 1977 through the landmark case Horton v. Meskill, which ruled that the state’s funding system violated the constitutional right to education. In response, the state legislature introduced the Guaranteed Tax Base (GTB) formula in 1975, which later evolved into the ECS system in 1988. Despite these efforts, achieving equal funding across districts remains elusive.

The Impact of Economic Factors on Education Funding

Connecticut’s ongoing pension debt has significantly affected education funding. Successive governors and state legislatures have struggled to adequately fund pension obligations, resulting in billions of dollars in debt. As mandatory pension contributions surged in the 1990s, education funding suffered as resources became increasingly scarce.

In 2017, state officials began a comprehensive approach to address this debt, including refinancing pension obligations and implementing a multi-year plan to enhance ECS funding. Despite these measures, critics highlight that the ECS program has only increased by $450 million since its inception, calling this growth insufficient to offset decades of stagnant funding.

The School and State Finance Project, a Connecticut-based education policy group, estimates that the ECS system would need an additional $99 million this fiscal year alone if adjusted for inflation. The Connecticut Conference of Municipalities (CCM) has publicly criticized the current administration, asserting that funding adjustments have led to a decline of over $400 million in adjusted ECS grants since Gov. Ned Lamont took office in 2019.

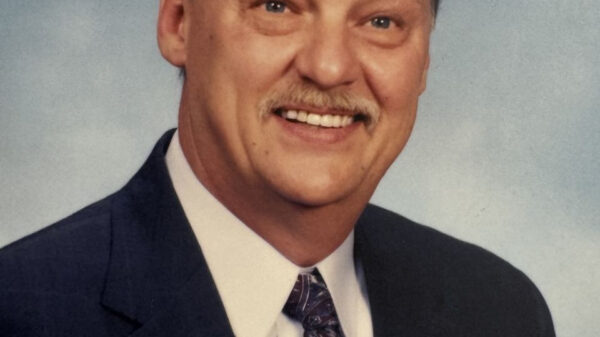

CCM Executive Director and CEO Joe DeLong stated, “Local leaders are being asked to do more with less, and the state’s leadership needs to be honest about the challenges our communities face. It’s time for real solutions that provide stable, predictable and sufficient funding.”

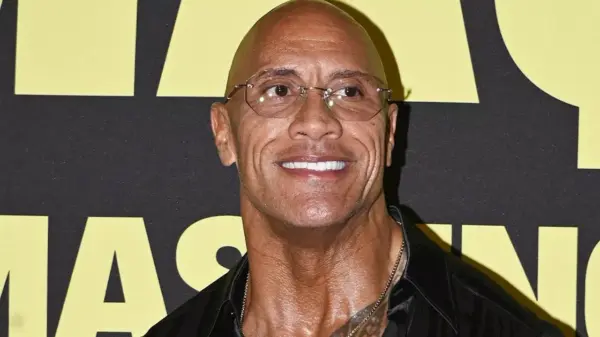

In response, Lamont emphasized his commitment to increasing both education and municipal aid while managing the inherited pension debt, stating, “My budgets prioritized significant municipal aid investments because that funding is about more than ensuring our unique towns and cities are incredible places to live, but because that funding supports our children’s education.”

The Future of ECS: Hold Harmless and Funding Cuts

A significant concern for the future of the ECS program is whether Connecticut will need to reduce education grants for some districts to allocate more funds to others. For decades, state officials have largely avoided this option, adhering to a “hold harmless” policy that ensures no district receives less funding than the previous year.

This approach was put to the test in the spring of 2023, when Lamont proposed an increase of over $80 million to the ECS program for the 2025-26 fiscal year. However, this plan also risked reducing funding for more than 80 communities, which would collectively lose nearly $10 million.

State Senator Cathy Osten, co-chairwoman of the Appropriations Committee, advocated for the continuation of the hold harmless policy, arguing that the ECS formula is flawed and could disproportionately affect poorer, rural communities in her New London County district. Many of these towns face high unemployment and declining student populations, complicating their ability to cut costs.

Ultimately, legislators opted to maintain funding for these districts for an additional two fiscal years, but the debate over the hold harmless provision is expected to resurface soon. As Connecticut navigates its complex educational funding landscape, the stakes remain high for students and communities relying on equitable access to quality education.