In a significant effort to address historical omissions, the Museum of Art and Light in Manhattan, Kansas, has unveiled an exhibition titled Crafting Sanctuaries: Black Spaces of the Black Great Depression South. This display re-examines the visual history of the Great Depression by highlighting the experiences of Black Southerners through the lens of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) photography collection. The exhibition, which runs until spring 2024, aims to broaden the narrative surrounding this pivotal time in American history.

The FSA was established in 1937 by the United States Department of Agriculture to aid rural communities impacted by the Great Depression. Under the leadership of government official Roy Stryker, the FSA initiated a photography project designed to generate public support for its initiatives. However, the images selected for dissemination predominantly featured White families, creating a narrow portrayal of rural America during this challenging period.

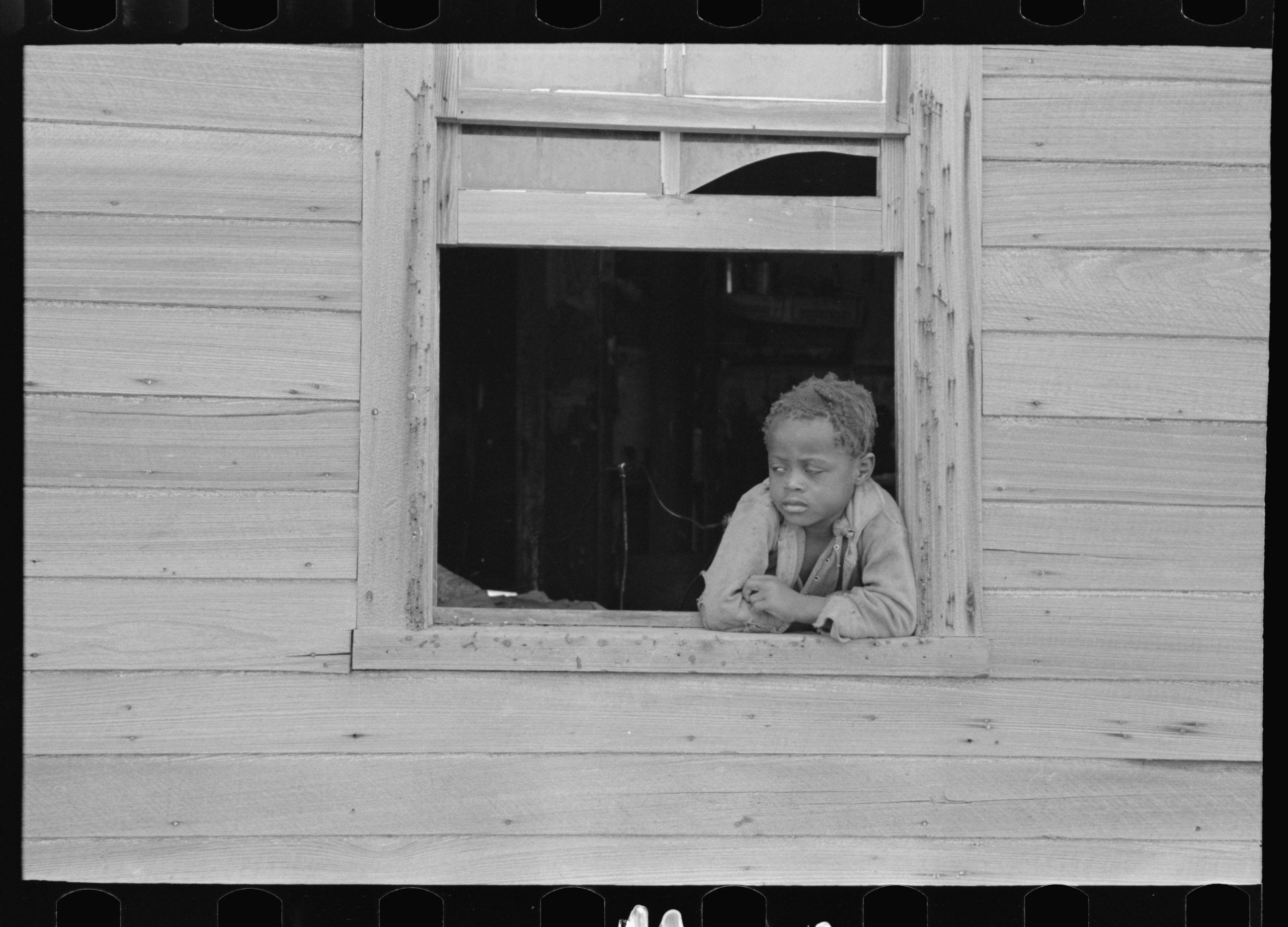

Curated by Tamir Williams, the exhibition presents a more inclusive view, focusing specifically on the lives of Black individuals and families documented by renowned photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Russell Lee. The photographs span six states, including Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Florida, Mississippi, and Missouri, showcasing intimate moments within Black communities, from private homes to public gatherings.

Williams, who approached the Art Bridges Foundation to curate the first in-house traveling exhibition, was inspired by previous research on the representation of Black individuals in FSA photography. They unearthed significant works, including Nicholas Natanson’s “The Black Image in the New Deal” and Sarah Boxer’s article “Whitewashing the Great Depression,” which highlighted the lack of visibility for Black and other non-White persons in the historical narrative.

During their investigation at the Library of Congress, Williams discovered images that portrayed small homes built by both Black and White laborers, particularly in La Forge, Missouri. This prompted them to delve deeper into the domestic lives of Black families beyond the confines of traditional representations. Williams expressed a desire to explore how Black Southerners crafted their unique spaces of beauty and community amid economic hardship and racial violence.

The exhibition’s photographs offer a poignant glimpse into the everyday lives of Black families. For instance, Jack Delano’s 1941 image of a tenant family near Greensboro, Alabama, captures a young family in their home, marked by the presence of newspaper clippings on the walls and a kitten at their feet. Associate curator Javier Rivero Ramos remarked on the emotional depth conveyed in such images, stating, “It seems like every conceivable emotion, thought, and event unfolding through the country is somehow refracted in the image.”

Complementing the exhibition is “Sanctuary in Motion,” a collaborative installation developed with the Yuma Street Cultural Center. Kristy Peterson, vice president of Learning, Engagement, and Visitor Experiences at the museum, emphasized the historical significance of Manhattan, Kansas, established by abolitionist settlers around 1855. This companion exhibit shares the story of Yuma Street and its importance as a sanctuary for families striving to create a better life.

Through Crafting Sanctuaries, Williams hopes to encourage viewers to appreciate the expansive definitions of beauty that Black Southerners adopted while crafting personal and communal spaces of refuge during a difficult era. As the exhibition unfolds, it serves as both a corrective to the historical record and a meditation on resilience, creativity, and community among Black Americans during the Great Depression.