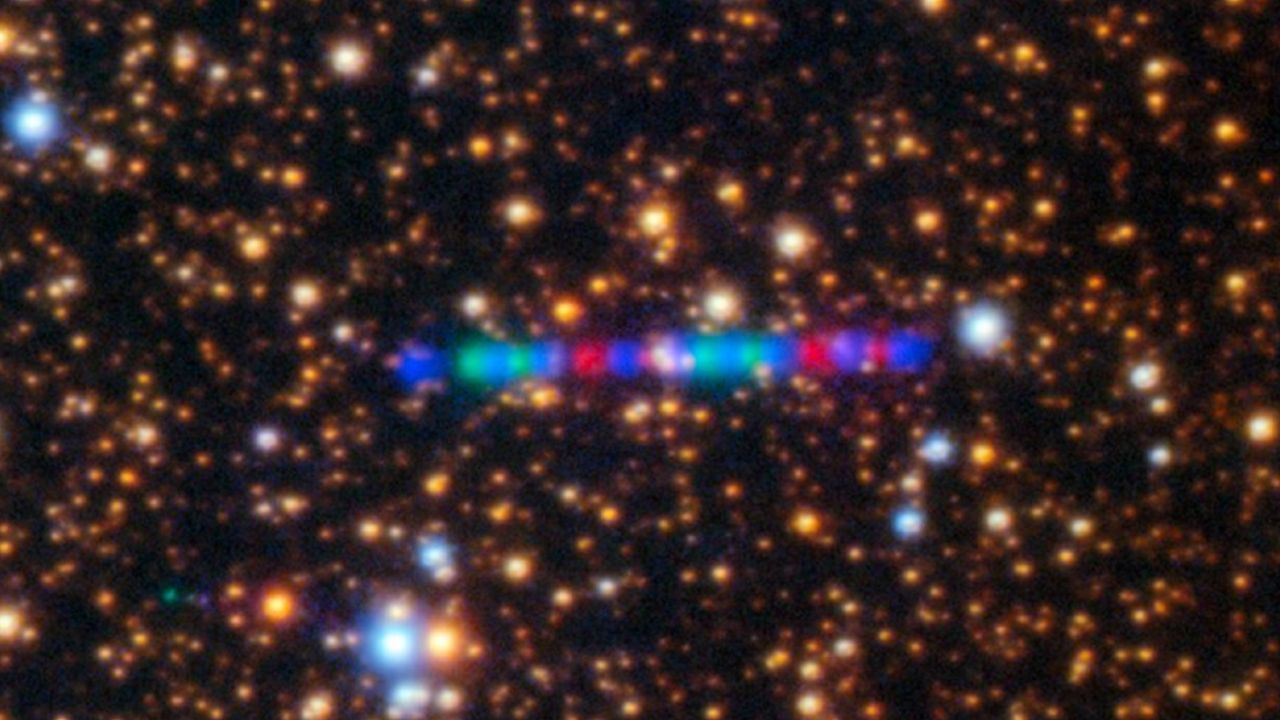

Two spacecraft are set to pass through the tail of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, providing a unique opportunity for scientific observation. A recent study by Samuel Grand and Geraint Jones, affiliated with the Finnish Meteorological Institute and the European Space Agency (ESA) respectively, suggests that the Hera and Europa Clipper spacecraft could gather valuable data as they approach the comet in late October.

3I/ATLAS, the third known interstellar object, has sparked various theories, from conspiracy claims of it being an alien spacecraft to more scientific proposals. The latest research recommends utilizing these two spacecraft, which are already on missions to different destinations within our solar system. Hera is en route to the Didymos-Dimorphos binary asteroid, while Europa Clipper aims to study Europa, one of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons.

Both spacecraft will pass “downwind” of 3I/ATLAS in the coming weeks. Hera has a window for observation between October 25 and November 1, while Europa Clipper’s window is from October 30 to November 6. This tight timeline presents a challenge, as neither spacecraft was originally designed for this kind of experiment. Nevertheless, they represent a significant chance to advance our understanding of the interstellar comet’s tail.

The tail of 3I/ATLAS has been growing since its discovery in early June, with recent observations indicating a massive outpouring of water particles. The comet is expected to reach perihelion, its closest approach to the Sun, on October 29. As noted in the study, capturing data from the tail involves more than just following the comet directly; the solar wind alters the trajectories of particles, creating a complex path that the spacecraft must navigate.

To estimate the path of cometary ions, the authors developed a model titled “Tailcatcher,” which predicts where ions will be based on varying solar wind speeds. Their calculations suggest that Hera and Europa Clipper would be approximately 8.2 million kilometers and 8 million kilometers away from the central axis of the tail, respectively. Although these distances are significant, they remain within a range that could allow for data collection.

A key limitation for Hera is that it lacks the instruments necessary to detect ions or the magnetic field changes associated with the comet’s tail. Conversely, Europa Clipper is equipped with a plasma instrument and a magnetometer, which are ideal for this investigation.

The potential for this mission relies heavily on timely coordination. It is uncertain whether mission controllers for either spacecraft will have sufficient time to adjust their operations for this unexpected opportunity. Should they succeed, they may achieve the historic milestone of directly sampling the tail of an interstellar comet, adding a remarkable chapter to space exploration.

The findings from this study underscore the importance of adaptability in scientific research. As the cosmos continually presents new mysteries, the scientific community remains poised to seize opportunities that further our understanding of the universe.