Following a deadly outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease in Harlem this summer, which resulted in seven fatalities and 90 hospitalizations, New York City lawmakers have introduced new legislation aimed at enhancing public health safeguards. The proposed regulations would require building owners to test their cooling towers—known to be primary transmitters of the disease—every 30 days, a significant reduction from the current requirement of every 90 days. During heat-related emergencies, testing would be mandated every 14 days.

While many see increased testing frequency as a necessary step, some public health experts argue that the legislation overlooks critical aspects of cooling tower management, particularly maintenance practices and the timing of water tests. According to Abraham Cullom, director of water safety and management at Pace Analytical, merely increasing testing frequency does not address the fundamental issue of how and when those tests are conducted.

Cullom emphasizes that testing conducted immediately after cleaning can yield misleading results. “You can throw as much testing at this as you want,” he stated, adding, “If you’re not doing other things that are actually controlling Legionella, the testing itself isn’t going to protect anyone.” He likened the current testing requirements to a weigh-in for boxers, where athletes are only measured at their lowest weight, failing to account for their overall performance and condition.

Janet Stout, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh and a noted authority on waterborne diseases, echoed Cullom’s concerns. She recounted a specific incident where a water sample from a cooling tower was rejected because it smelled strongly of chlorine, suggesting it was taken shortly after a cleaning. “When you test after a cleaning, all it does is confirm that you’ve cleaned the tower,” Stout explained. She advocates for testing to occur before cleaning, allowing for a more accurate assessment of whether treatment methods are effective.

The proposed legislation, co-authored by Lynn Schulman, chair of the City Council’s health committee, is set to be reviewed in an upcoming oversight hearing scheduled for August 25, 2023. Schulman declined to comment on whether further measures will be considered beyond more frequent testing.

Currently, city laws mandate that building owners monitor the chemical and bacteriological content of water in their cooling towers, but they are only required to report test results for Legionella bacteria every 90 days. Former city health official Don Weiss suggested that requiring more frequent reporting—ideally on a daily or weekly basis—could help the city promptly identify cooling towers at risk of Legionella growth. “It would probably be a bit of an expense,” Weiss noted, “but once you set the system up, it would work seamlessly.”

Cooling towers, typically located on rooftops, play a vital role in a building’s heating and cooling systems. They circulate water that absorbs heat from the building’s interior and evaporates warm water, creating a potential breeding ground for Legionella bacteria, especially at elevated temperatures. If this bacteria becomes airborne and is inhaled, it can lead to Legionnaires’ disease.

In response to a previous outbreak in 2015, New York City enacted regulations requiring all building owners to register their cooling towers, hire professionals for management, and develop maintenance plans. The laws also granted the city health department authority to inspect cooling towers and verify that building owners were adhering to testing and maintenance protocols.

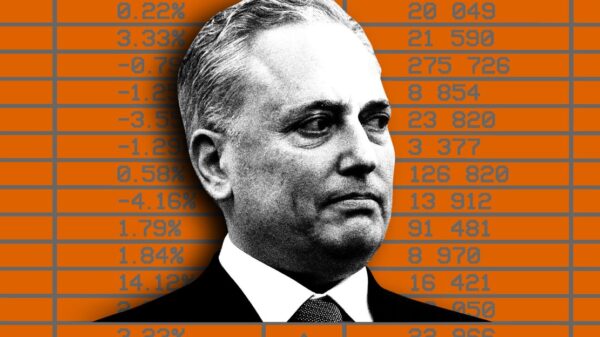

However, a recent analysis by Gothamist revealed that in the months leading up to this summer’s outbreak, the health department was on track to conduct fewer than half of the inspections performed in 2017, the year the regulations were implemented. Out of approximately 5,000 registered cooling towers, around 30% had not been inspected since 2023. The health department attributed this decline to a shortage of inspectors, despite an increase in funding for the unit.

During a press conference in late August, Michelle Morse, the city’s health commissioner, assured the public that the city had adequate staff to respond to the outbreak. She also noted ongoing efforts to recruit additional inspectors to bolster monitoring capabilities.

Stout argues that more frequent inspections by city officials could help ensure that building owners are adhering to the spirit of the law, rather than merely meeting minimum reporting requirements. “Someone has to be looking over their shoulder,” she said, advocating for better funding for public health to enhance inspection efforts.

As the city grapples with the fallout from the outbreak, the proposed legislation serves as a first step. Yet, experts warn that meaningful action will require a comprehensive approach that goes beyond testing to encompass rigorous maintenance and oversight.