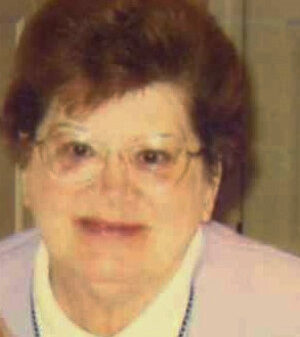

Nurses across California are raising serious concerns about the presence of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents in hospitals, claiming that their activities are disrupting patient care. One incident in June at the UCLA emergency room starkly illustrated these issues when Dianne Sposito, a 69-year-old nurse with over 40 years of experience, was blocked from attending to a distressed immigrant patient by an ICE agent.

The situation escalated rapidly when the agent, who was not readily identifiable, brought a woman already in custody into the emergency room. As the patient screamed and struggled, Sposito attempted to assess her condition, only to be obstructed by the agent, who insisted that she refrain from providing care. “I’ve worked with police officers for years, and I’ve never seen anything like this,” Sposito said. “It was very frightful because the person behind him is screaming, and I don’t know what’s going on with her.”

After the incident, hospital administration conducted a meeting where it clarified that ICE agents are permitted only in public areas of the hospital, not in emergency rooms. Despite these guidelines, Sposito expressed her belief that they are insufficient, highlighting the heightened tension surrounding such encounters. She remarked, “That patient could be dying.”

This incident is part of a troubling trend. According to Mary Turner, president of the National Nurses United, the largest organization of registered nurses in the United States, the presence of ICE agents in hospitals has increased significantly since the summer. Turner stated, “The presence of ICE agents is very disruptive and creates an unsafe and fearful environment for patients, nurses, and other staff.”

While there is no nationwide data tracking ICE’s activities in hospitals, regional unions have reported an uptick in such encounters. Sal Rosselli, president emeritus of the National Union of Healthcare Workers, noted that members have reported ICE agents or contractors inside hospitals more frequently than ever before.

Concerns extend beyond the immediate impact on patient care. Nurses have reported that ICE agents sometimes prevent patients from contacting family members and have even listened in on conversations between patients and healthcare workers, actions that violate the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). “Hospitals are supposed to discharge a patient with instructions for the patient or whoever will be caring for them,” Turner emphasized.

The rise in ICE activity within healthcare settings follows an executive order by former President Donald Trump, which rescinded the long-standing designation of hospitals, healthcare facilities, and schools as “sensitive locations” where immigration enforcement was restricted. This change has raised fears among healthcare providers that it will deter individuals from seeking necessary medical care.

In a joint statement, George Gresham, president of the 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East, and Patricia Kane, executive director of the New York State Nurses Association, condemned the situation, stating, “Allowing ICE undue access to hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and other healthcare institutions is both deeply immoral and contrary to public health.”

Policies regarding immigration enforcement vary widely among healthcare facilities. In California, county-run public healthcare systems must adhere to guidelines established by the state’s attorney general, which limit information sharing with immigration authorities and require facilities to inform patients of their rights. Other healthcare entities, however, are merely encouraged to adopt similar policies.

In a notable case, Milagro Solis Portillo, a 36-year-old Salvadoran woman, was detained by ICE outside her home and subsequently hospitalized at Glendale Memorial. During her stay, ICE agents monitored her closely, restricting her access to visitors and interfering with her communication with medical staff, which violated her rights as a patient. Her attorney, Ming Tanigawa-Lau, expressed frustration at ICE’s refusal to disclose the legal basis for their actions, which included barring access to her attorney.

Glendale Memorial responded to the situation, stating that the hospital cannot legally restrict law enforcement from being present in public areas, such as the lobby. Tricia McLaughlin, assistant secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, asserted that ICE does not conduct enforcement operations that interfere with medical care, claiming they provide comprehensive medical care from the moment someone enters ICE custody.

The federal government has taken a strong stance against healthcare workers who challenge ICE’s presence. In August, the U.S. Department of Justice charged two staff members at the Ontario Advanced Surgical Center in San Bernardino County, California, with assaulting federal agents. The incident occurred on July 8 when ICE agents pursued three men at the facility.

As the legal and ethical implications of ICE’s presence in healthcare settings continue to unfold, nurses and healthcare professionals remain committed to advocating for the rights of their patients. The trial for the charged healthcare workers is scheduled to begin on October 6, 2023, marking a significant moment in the ongoing debate over immigration enforcement in medical facilities.