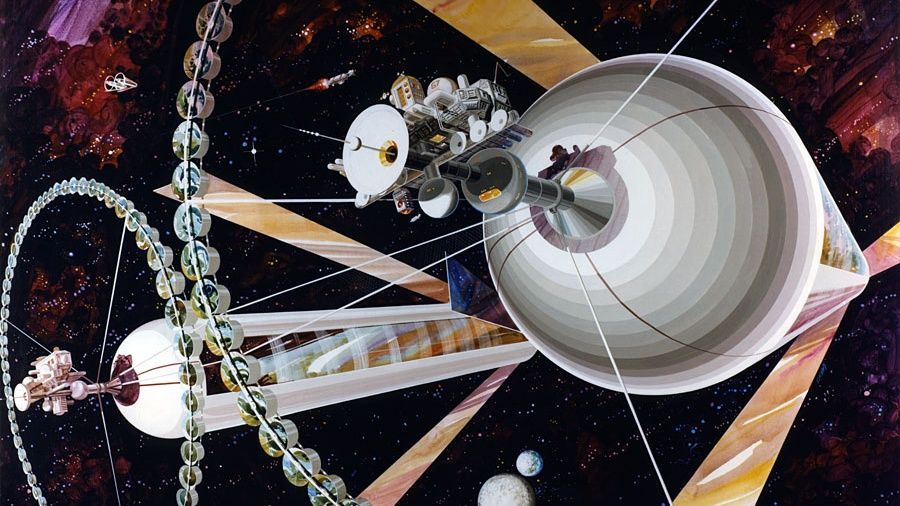

The dream of living in cities beyond Earth, once championed by physicist Gerard K. O’Neill, remains largely unrealized as of 2025. O’Neill, a professor at Princeton University, envisioned vast cylindrical habitats that could support millions of people, allowing them to gaze down upon Earth from their celestial homes. His ideas captured public interest in the 1970s, leading to appearances on television, a best-selling book, and even testimony before the U.S. Congress.

O’Neill articulated his vision in the influential book, “The High Frontier,” published in 1976. He proposed constructing these habitats at the L5 Lagrange point, a gravitationally stable location between Earth and the Moon, with initial feasibility projected between 1990 and 2005. This ambitious concept inspired the formation of the L5 Society, which adopted the motto: “L5 by ’95!”

O’Neill’s designs featured rotating habitats meant to simulate gravity through centrifugal force, allowing for comfortable living conditions. His most ambitious model, “Island Three,” would have measured four miles (6.4 kilometers) in width and 20 miles (32 kilometers) in length, providing over 500 square miles (1,294 square kilometers) of living space. This space would include homes, recreational areas, and green parks.

Despite the allure of these concepts, the reality of human habitation in space remains starkly different. As of now, only 290 astronauts have ventured into the cosmos, primarily aboard the International Space Station and other simpler space stations like Russia’s Mir or China’s Tiangong. The dream of space cities has not materialized, and many view it as overly optimistic.

The vision for space habitats emerged during a transformative period in history. In 1969, O’Neill began teaching introductory physics at Princeton. The excitement of the Apollo program was dampened by growing disillusionment surrounding the Vietnam War, prompting many students to question the value of a career in science and technology. O’Neill sought to inspire his students by posing engineering challenges that integrated economic and social issues, asking whether the surface of a planet was truly the best place for a technological society.

His ideas were influenced by the Club of Rome’s 1972 report “Limits to Growth,” which warned of overpopulation, environmental degradation, and resource depletion. O’Neill argued that if Earth’s capacity was being exceeded, humanity should seek alternatives beyond the planet. Space offers abundant resources, solar energy, and the potential for clean industry.

O’Neill believed that the 1970s possessed the technology necessary to develop these habitats, stating that “Island Three” could be built in the early years of the next century. He envisioned mining operations on the Moon and near-Earth asteroids, utilizing a technology called a “mass driver.” This electromagnetic system would enable rapid transport of materials from celestial bodies to the L5 point, paving the way for future construction.

While O’Neill’s vision was grand, significant challenges hindered its realization. The most notable obstacle was the failure of the space shuttle program, which fell short of its goal to conduct hundreds of launches annually. Between its first flight in 1981 and its last in 2011, the program managed only 135 missions. This limited capacity significantly impacted the potential for developing the necessary infrastructure for space cities.

Additionally, the estimated cost of constructing a 20-mile-long (32-kilometer-long) habitat was around $200 billion in the 1970s, roughly equivalent to $1.1 trillion in 2025. Such financial demands pose further barriers to the realization of O’Neill’s dreams.

Social concerns also complicate the prospect of space habitats. With over 8 billion people currently residing on Earth, relocating even tens of millions to space would not alleviate overpopulation. Moreover, questions arise regarding who would have access to these extraterrestrial communities. Historically, social inequities suggest that wealthier individuals would be more likely to escape Earth’s challenges, potentially exacerbating the divide between rich and poor nations.

While space habitats could provide a refuge from Earth’s disasters, they also represent a retreat from addressing pressing terrestrial issues. The failure of O’Neill’s dream serves as a reminder of the ambitious vision humanity once held for its technological future. From the perspective of the 1970s, the 21st century promised vast possibilities, yet today, the world grapples with war, authoritarianism, and environmental crises, prompting reflection on whether society has failed to meet its potential.

In summary, O’Neill’s aspirations for cities in space reflect a bygone era of hope and innovation. As humanity continues to navigate complex global challenges, the dream of living among the stars may remain just that—a dream, overshadowed by the realities of today’s world.