As the UK observes Black History Month, discussions surrounding reparations for transatlantic enslavement have resurfaced. The debate often becomes mired in contention, with critics arguing that reparations are too complicated or divisive. This was evident during Keir Starmer‘s visit to a Pacific island nation last year, where he faced demands for justice related to historic wrongs. Instead of garnering positive headlines about Commonwealth partnerships, his trip was overshadowed by calls for reparations, to which he responded by stating it was “not on the agenda.”

In an effort to explore the complexities of reparative justice, I spoke with Kojo Koram, a lecturer at the School of Law at Birkbeck, University of London. He emphasized that the public discourse often overlooks substantial efforts to define reparations beyond mere financial compensation. The historical context of reparations remains critical to understanding current debates.

Historical Context of the Reparations Debate

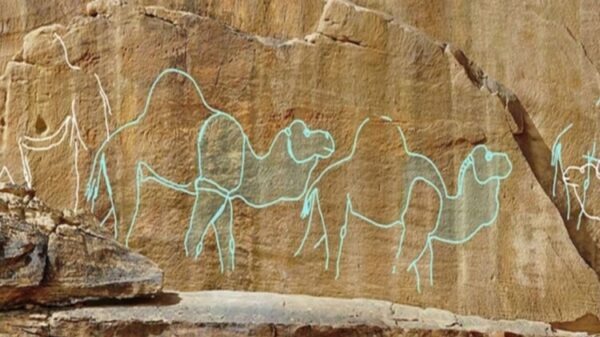

The movement for racial justice gained significant traction in the UK during the summer of 2020, with over 260 towns and cities witnessing protests that historians described as the most extensive anti-racist demonstrations since the abolition of slavery. At the forefront of these protests was a call for Britain to confront its history of transatlantic enslavement and to provide reparations.

Despite the momentum, the UK government has yet to issue a formal apology for slavery. In a notable instance, former Prime Minister Tony Blair expressed “deep sorrow” in 2006, but this was not recognized as an official apology by Caribbean nations. Some British institutions took steps towards reparative justice in 2020. The Bank of England issued an apology, while institutions such as Lloyd’s of London and the Church of England committed to reparations.

However, the initial wave of commitments has not led to sustained action, and the backlash against reparations has stifled progress. Many see the figures associated with reparations—such as a recent study estimating the UK’s liability at approximately $24 trillion (£18.8 trillion)—as insurmountable rather than a reflection of historical injustices.

Reparations: A Broader Perspective

Koram points out that the UK has historically compensated enslavers rather than the enslaved. Following the abolition of slavery, the British government borrowed £20 million—equivalent to 40% of the Treasury’s annual income at the time—to compensate slave owners for their “lost property.” This debt was ultimately paid off by British taxpayers until 2015.

Starmer’s avoidance of the reparations issue raises concerns about the political class’s willingness to engage with the topic. While he focuses on contemporary challenges, Koram argues that the reparations movement is intrinsically linked to these very issues. He believes that reparative justice goes beyond financial compensation and includes restructuring the existing global power dynamics that perpetuate inequality today.

Koram illustrates this point by discussing climate policy, suggesting that reparations could involve facilitating equitable arrangements between the global north and south to address climate change. He emphasizes that the demands for reparative justice encompass various forms, including economic restructuring and legal reforms.

Amidst the debate, frameworks for reparations exist. The Caribbean Community (Caricom) has proposed a 10-point plan that includes creating museums, addressing health crises, and canceling historical debts. This framework underscores the connection between historical injustices and modern societal challenges.

Koram reminds us that the legacy of slavery continues to shape contemporary society. The ideologies born from the transatlantic slave trade still affect how individuals are viewed and treated in various institutions today. He posits that the demand for racial equality is increasingly intertwined with calls for reparative justice, highlighting the need for a more nuanced understanding of the past and its ongoing impact.

As discussions about reparations continue, it is clear that the movement is gaining momentum. Koram’s insights reveal that the issues surrounding reparative justice are far from resolved, pressing the need for urgent dialogue and action in addressing these historical grievances. The past, he asserts, is not merely a relic; it is an ongoing influence that shapes our present and future.