In 1925, two unconventional researchers, a hat maker and a former railroad clerk, made a groundbreaking discovery that significantly advanced the field of cancer research. Their findings, published in the esteemed medical journal The Lancet, hinted at a potential solution to the complex problem of cancer, igniting excitement within the scientific community and beyond.

On the day the studies were released, a crowd gathered outside The Lancet offices in London, driven by rumors that a cancer “germ” had been observed under a microscope for the first time. As reported by Peter Vischer in Popular Science, the crowd grew increasingly impatient, filled with anticipation for a revelation that could change the understanding of one of humanity’s most feared diseases.

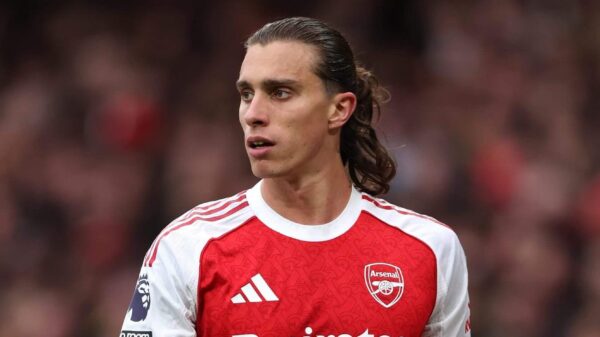

The two researchers, Joseph Edwin Barnard and William Ewart Gye, were not traditional figures in the medical field. Barnard, a respected hatter in London, balanced his daytime work with late nights in his private laboratory, where he developed innovative microscopy techniques. Gye, on the other hand, took a more mysterious route to research. Originally named William Ewart Bullock, he adopted the surname Gye in 1919 for reasons that remain unclear, although theories suggest a connection to a benefactor or his suffragette wife.

Their collaboration began when Gye, equipped with extensive knowledge in experimental biology and germ theory, joined forces with Barnard, whose expertise with microscopy allowed them to explore cancer at a microscopic level. Their combined efforts built on the foundation laid by pioneers like Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur, who had previously identified germs responsible for diseases like cholera and anthrax.

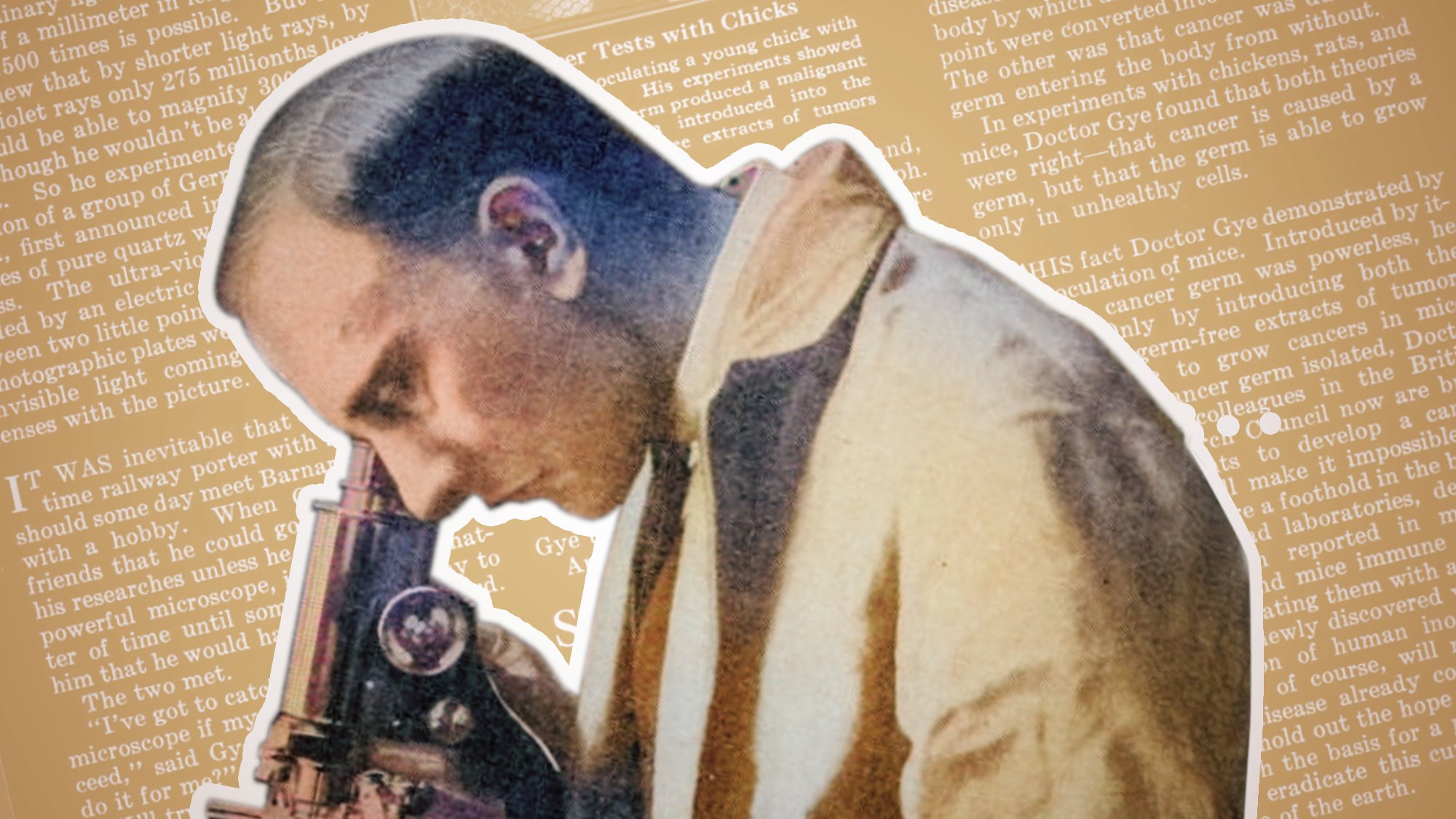

In their research, Barnard and Gye discovered what they termed “particulate bodies” associated with cancerous cells. Barnard’s article in The Lancet detailed the visual evidence captured under his advanced microscope. He observed variations in cell wall thickness, suggesting that a virus might replicate within these walls. This finding raised hopes that a vaccine for cancer could be developed.

Gye’s contributions included a two-factor theory of cancer, which he presented in the same journal. He posited that cancer did not arise from a single germ but rather from the interaction between damaged cells and a virus. His experiments demonstrated that when he inoculated young chicks with both a cancer virus and a tumor extract, tumors reliably formed.

This innovative approach marked a significant shift in cancer research. Instead of solely identifying germs linked to diseases, Gye and Barnard’s work suggested a more complex relationship between viruses and cellular damage. Their findings were not entirely accurate by today’s standards, yet they provided a new direction for cancer research, emphasizing the need to consider multiple factors in understanding the disease.

A century later, the legacy of Gye and Barnard’s work continues to influence cancer research. The understanding of cancer has evolved significantly since the 1920s. Today, researchers recognize that cancer is a multifaceted group of diseases driven by genetic mutations and various environmental factors. Instead of searching for a singular germ, modern scientists utilize advanced tools like electron microscopes to investigate the intricate cellular mechanisms that govern growth and death.

Despite the complexity of cancer research, significant strides have been made in prevention, early detection, and treatment. While cancer remains a leading cause of death worldwide, advancements in treatment protocols have improved patient outcomes and instilled hope for future breakthroughs.

Ultimately, the partnership between Barnard and Gye exemplifies how passion and determination can lead to remarkable discoveries, even among those who are not entrenched in the medical establishment. Their story serves as a reminder of the importance of accessibility in scientific research and the potential for unconventional thinkers to drive progress in understanding and combating diseases like cancer.