U.S. President Donald Trump faced backlash after praising Liberian President Joseph Boakai for his command of the English language during a recent meeting with five African leaders at the White House. Trump remarked on Boakai’s “beautiful” English and asked where he learned to speak so well, despite English being the official language of Liberia.

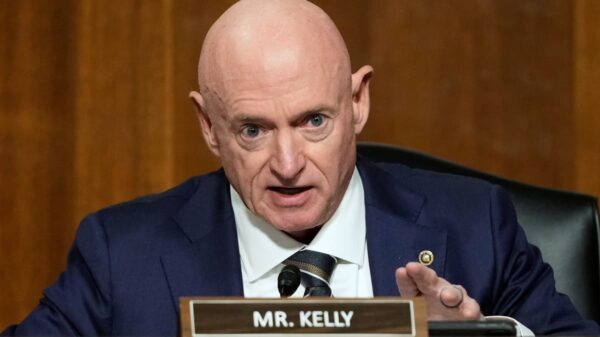

This comment prompted criticism from various quarters, as many found it reflective of a condescending attitude towards African leaders. Boakai, educated in Liberia, responded with the name of his institution, which seemed to intrigue Trump further. He later noted, “I have people at this table who can’t speak nearly as well.”

Liberia’s complex history adds context to the exchange. Founded in 1822 by the American Colonization Society to resettle freed slaves, Liberia declared its independence in 1847. The country boasts a rich tapestry of languages, with English serving as the official tongue.

Archie Tamel Harris, a Liberian youth advocate, expressed his concern over Trump’s comments, stating, “I felt insulted because our country is an English-speaking country.” He emphasized that such remarks perpetuate stereotypes about Africans lacking education. Another Liberian diplomat, who preferred to remain anonymous, described the comment as “not appropriate” and “condescending” towards an African president from an English-speaking nation.

Responses from African leaders reflected a range of opinions. South African politician Veronica Mente questioned Boakai’s decision to remain seated, implying he could have taken a stand against the perceived disrespect.

In defense of Trump, the White House Press Office asserted that the president’s remarks were well-received. Massad Boulos, senior advisor for Africa, stated, “The continent of Africa has never had such a friend in the White House as they do in President Trump.” White House deputy press secretary Anna Kelly emphasized that Trump’s comment was a “heartfelt compliment,” suggesting that he has significantly contributed to global stability and support for African nations.

Liberia’s Foreign Minister Sara Beysolow Nyanti offered a different perspective, stating that there was “no offense” taken by Boakai. She argued that many do not grasp the linguistic diversity of Africa, adding that Trump’s observation regarding American influence on Liberian English was simply an acknowledgment of a shared linguistic heritage.

This incident is not the first time Trump has commented on the English language abilities of foreign leaders. In previous diplomatic meetings, he has similarly praised other leaders for their English proficiency. During a press conference with German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, Trump inquired whether Merz’s English was as good as his German, to which Merz humorously responded that he tries to understand and speak as well as he can.

Trump has made the promotion of the English language a cornerstone of his “America First” agenda. In 2015, he stated that the U.S. is “a country where we speak English” and in March 2024, he signed an executive order establishing English as the official language of the United States.

Despite the controversy surrounding his comments, Trump appeared to have a positive reception from the African leaders he met with, including those from Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, and Senegal. During the discussions, he praised their nations as “vibrant places” rich in minerals and natural resources, urging investment in these countries. In a show of goodwill, Boakai remarked that Liberia “believes in the policy of making America great again.”

As this meeting continues to draw reactions, it underscores the complexities in diplomatic relations, particularly when cultural sensitivities are involved.