Research has unveiled that Great Tits, small yellowish songbirds commonly found in European woodlands, exhibit more intricate social behaviors than previously understood. Published on July 30, 2023, in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the study highlights that not all pairs of Great Tits separate after the breeding season. Instead, many remain together through the winter, suggesting that avian relationships are influenced by complex social interactions.

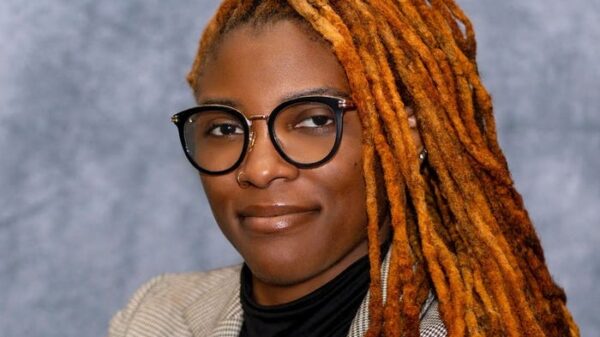

The study, led by Adelaide Daisy Abraham, a behavioral ecologist at Oxford University, tracked individual Great Tits in the woodlands near Oxford. Researchers attached small radio tags to monitor the birds’ movements and social interactions at various feeders set up for the study. Over a three-year period, they gathered data on which pairs associated with one another and the frequency of these interactions.

While it was previously believed that the formation of pairs was largely random and based on proximity, the findings indicate that the decision to stay together or separate hinges more on social dynamics than mere location. “Our results show that bird relationships are far from static,” Abraham noted, emphasizing that the phenomenon of “divorce” among these birds is not merely a seasonal occurrence, but rather a socially driven process that unfolds over time.

Divorce Trends and Social Interactions

Surprisingly, the research found that signs of separation among Great Tit couples can emerge as early as late summer, with divorce rates increasing throughout the winter months. Birds that eventually part ways show decreased interactions at feeders compared to those that remain together. “Those divorcing birds, they, from the start, are already not associating as much as the faithful birds,” Abraham explained in an interview with NPR.

Although the study outlines these behaviors, it does not provide a clear rationale for why some pairs choose to break up. The researchers suggest that a range of factors may influence these decisions, including social competition and the advantages of finding new partners. Questions remain about whether divorced birds are as successful in future mating or if they display different parenting patterns.

Future Research Directions

The study raises critical questions that warrant further investigation. For instance, do divorced Great Tits experience better mating opportunities, and are they affected by competition from other birds? The authors advocate for more extensive studies that could shed light on these social processes. “Following these individual birds across seasons and over many years allows us to see how relationships form and break down in nature in a way that short-term studies wouldn’t,” said Josh Firth, senior author and behavioral ecologist at the University of Leeds.

This research enhances our understanding of non-human intelligence and social dynamics in the animal kingdom. As the study highlights, there is a great deal happening in the flocks of birds that inhabit our environment, enriching our appreciation of their behaviors and interactions. The complexities of Great Tit relationships serve as a reminder that even the smallest creatures can exhibit profound social structures, offering insights into the broader patterns of life on Earth.