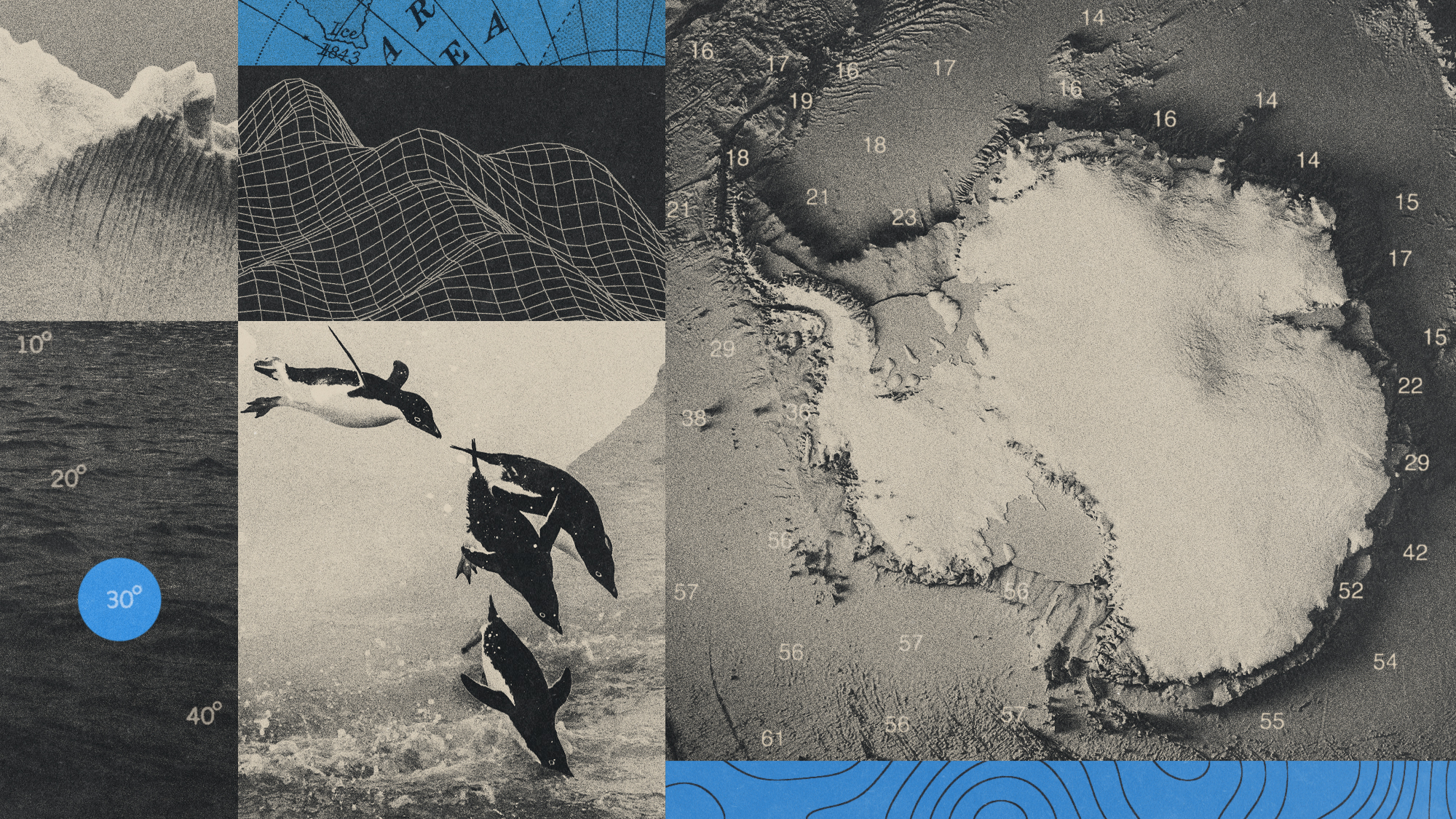

Recent research has uncovered the presence of hundreds of underwater canyons beneath Antarctica, some extending over 4,000 meters (more than 13,000 feet) deep. These complex geological formations play a crucial role in global climate patterns and ocean circulation, underscoring the need for further study to enhance climate models and predictions.

Mapping the Hidden Depths

According to a study published in the journal Marine Geology, scientists have identified 332 underwater canyons in Antarctica. The research highlights that these canyons resemble those found in other parts of the world but are notably larger and deeper due to the extensive influence of polar ice and the substantial volumes of sediment carried by glaciers to the continental shelf.

David Amblàs, a researcher with the Consolidated Research Group on Marine Geosciences at the University of Barcelona, noted that the canyons exhibit significant differences between eastern and western Antarctica. The eastern canyons are characterized by intricate, branching structures with wide U-shaped profiles, while those in the west are shorter and steeper, forming sharp V-shaped cuts. This geological diversity suggests that the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is likely much older than its western counterpart.

Implications for Climate Science

The implications of these findings are substantial. Researchers suggest that Antarctic canyons may have a more pronounced impact on ocean circulation, ice-shelf thinning, and global climate change than previously understood. Areas such as the Amundsen Sea and parts of East Antarctica are particularly vulnerable.

Submarine canyons are vital to various ecological, oceanographic, and geological processes worldwide. They facilitate the exchange of water between the deep ocean and the continental shelf, enabling cold, dense water formed near ice shelves to flow into the deep ocean. This process is essential for creating what is known as Antarctic Bottom Water. Conversely, these canyons also transport warmer ocean waters toward the coastline, helping to stabilize Antarctica’s interior glaciers.

Despite their importance, submarine canyons remain a largely overlooked aspect of climate change science. Less than one-third of the seafloor has been adequately mapped, leaving many canyons unexplored and unstudied. Omitting these water-transporting canyons from climate models limits their accuracy in predicting ocean and climate changes. Currently, scientists estimate there are approximately 10,000 submarine canyons globally, with many still awaiting exploration, particularly in polar regions.

To improve understanding of ocean circulation and its broader climate implications, comprehensive mapping of the seafloor is essential. As research continues, the significance of these underwater canyons in climate science will likely become increasingly clear, highlighting their role in shaping both regional and global climate dynamics.