A recent trial reveals that a daily pill of baricitinib may significantly slow the progression of type 1 diabetes, although stopping the treatment leads to a loss of its benefits. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Vienna, the findings emphasize the need for ongoing treatment to maintain therapeutic effects.

In 2023, a study conducted in Australia demonstrated that baricitinib, commonly prescribed for conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and alopecia, could help preserve the body’s insulin production in individuals recently diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. The follow-up trial assessed participants who had stopped taking the medication, revealing a decline in insulin production and less stable blood sugar levels.

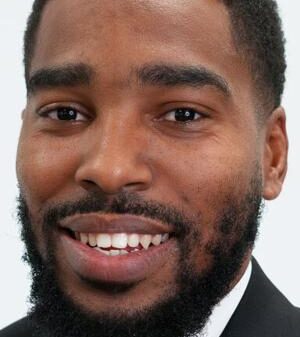

Michalea Waibel, a researcher from St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research, described the results as a “really exciting step forward.” She noted that this oral treatment allows individuals with type 1 diabetes to be less reliant on insulin injections and experience fewer daily management challenges. Waibel stated, “For the first time, we have an oral disease-modifying treatment that can intervene early enough to allow people with type 1 diabetes to be significantly less dependent on insulin treatment.”

From 2019 to 2022, nearly 4 in every 1,000 young people and 5 in every 1,000 adults in the U.S. reported having type 1 diabetes, according to previous studies. Waibel explained that baricitinib is unique among agents shown to preserve beta cell function because it is taken orally, is well-tolerated, and has proven efficacy.

The trial involved 91 participants aged 10 to 30 who had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes within the last 100 days. Participants were administered either a daily dose of 4mg of baricitinib or a placebo for 48 weeks. Throughout the trial, researchers monitored C-peptide levels, continuous glucose monitoring, and HbA1c levels to evaluate insulin production and blood sugar control.

Results indicated that those taking baricitinib preserved insulin-producing beta cell function and reduced blood glucose fluctuations. After treatment cessation, however, insulin production declined, with C-peptide levels dropping from 0.65 in the baricitinib group to 0.49 after 72 weeks, and further to 0.37 at 96 weeks. The findings showed that the need for insulin treatment increased significantly after stopping the medication, diminishing the positive effects seen during treatment.

Additionally, the study highlighted a deterioration in glucose control following the discontinuation of baricitinib. While differences in time spent within safe glucose ranges and blood glucose variability were noted during treatment, these were not statistically significant after participants stopped taking the drug.

The trial also examined various factors to identify predictors of treatment response but found no clear characteristics that distinguished responders from non-responders. This included age, specific immune system genes known as human leukocyte antigens (HLA), body mass index (BMI), or the number of autoantibodies present. Approximately two-thirds of participants taking baricitinib met response criteria, and there were no new safety concerns reported during the follow-up period.

Waibel expressed optimism for future research, stating, “If we can identify people at high risk of developing type 1 diabetes with genetic tests and blood markers, they could be offered treatment even earlier to prevent the disease from taking hold in the first place.” She anticipates that larger phase III trials of baricitinib will begin soon, targeting individuals newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and those in earlier disease stages to delay insulin dependence.

If successful, approval for baricitinib as a treatment for type 1 diabetes could be achieved within five years.