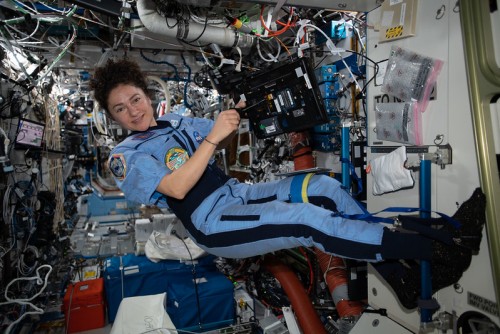

A recent study reveals that the structure and function of astronauts’ arteries remain stable for up to five years following long-duration missions aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Conducted by a team of researchers and published in the Journal of Applied Physiology, the findings provide important insights into the long-term health of astronauts after their return to Earth.

Examining Arterial Health in Space

Research indicates that while astronauts experience significant physiological changes during spaceflight, including effects on their cardiovascular system, the long-term consequences have been less understood. The study involved 13 NASA astronaut volunteers, who were aged between their late 30s and late 50s during their missions. These astronauts spent time ranging from four months to nearly one year in space.

Using ultrasound imaging, researchers assessed the carotid and brachial arteries of the volunteers before launch, during their missions, immediately after returning, and up to three times over five years post-mission. This comprehensive analysis also included a review of the astronauts’ medical data, comparing it to pre-flight information.

Key findings showed that most markers of inflammation and oxidative stress in blood and urine samples taken during spaceflight returned to normal within just one week of landing. Notably, there was no increase in carotid artery thickening or stiffness, both of which are indicators of potential cardiovascular disease.

Long-term Observations and Lifestyle Factors

Researchers also noted that brachial artery vasodilation, an important measure of vascular health, remained stable over time. Although total cholesterol and glucose levels increased moderately over the seven years of observation, hemoglobin A1C levels did not rise, indicating that the risks associated with heart disease and diabetes did not escalate as a result of space travel.

Using a risk estimation tool designed for the general population, the study found that the likelihood of developing heart disease increased from 2.6% to 4.6% from pre-flight to five years after returning. However, when the tool was adjusted to reflect a population with health characteristics similar to astronauts, the risk increased by only an additional 0.5%.

Interestingly, the astronauts reported maintaining active lifestyles after their missions, including those who had retired from the astronaut corps. The research team emphasized that the natural aging process of the astronauts contributed significantly to the increase in predicted health risks.

The researchers concluded, “We report that most indices of arterial structure and function in ISS astronauts were not different than preflight and that there were no signs, symptoms, or diagnoses of cardiovascular disease during the first five years after returning to Earth from long-duration spaceflight.” This suggests a remarkable resilience of the cardiovascular system in astronauts, despite the challenges posed by microgravity.

For those interested in the full study, titled “Arterial Structure and Function in the Years after Long-duration Spaceflight,” it has been highlighted as one of the best articles by the American Physiological Society this month. Further details can be found through their Newsroom, which also provides additional research highlights.

The American Physiological Society brings together a global community of over 10,000 biomedical scientists and educators, dedicated to advancing scientific discovery and improving health through collaborative research.