Relatives of Indian nurse Nimisha Priya, who is on death row in Yemen, are urgently seeking to commute her death sentence, with her execution scheduled for March 6, 2024. The case has drawn significant attention in India, where families and human rights advocates are rallying to prevent what they view as a miscarriage of justice. Priya was sentenced to death for the murder of her former business partner, a Yemeni national, whose body was found in a water tank in 2017. A Yemeni court issued the death penalty in 2020, and since then, her family has strived to secure her release, facing challenges exacerbated by the lack of formal diplomatic relations between India and the Houthi authorities who control the capital, Sanaa.

As the execution date approaches, India’s media has extensively covered Priya’s plight. Human rights organizations, including Amnesty International, have publicly urged the Houthis to halt the execution. On March 4, 2024, Amnesty called for an immediate moratorium on all executions in Yemen, stating, “The death penalty is the ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment.”

According to Samuel Joseph, a social worker assisting Priya’s family, there exists a possibility for clemency under Yemen’s Islamic laws. If the victim’s family pardons Priya and accepts a financial compensation known as “diyah,” her sentence could be commuted. Joseph expressed optimism about the situation, citing active efforts from the Indian government and support from the community: “I’m spiriting the efforts here, and by god’s grace, we got people who are helping.”

Priya’s trial has been marred by concerns regarding due process. It was conducted in Arabic, and she did not have access to a translator, complicating her defense. Her family asserts that she acted in self-defense against an abusive partner who withheld her passport, leaving her vulnerable in a war-torn country.

Struggles for Justice in Yemen

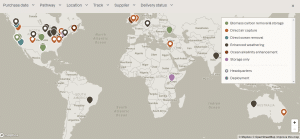

The Save Nimisha Priya Action Council, established in 2020, has been pivotal in raising funds and negotiating with the victim’s family. Activist Rafeek Ravuthar noted the difficulty of negotiations, stating, “The reality is that there is no Indian embassy, there is no mission in this country.” So far, the council has raised approximately 5 million rupees (nearly $58,000) to assist in Priya’s legal battles.

In recent days, politicians from Priya’s home state of Kerala have called on Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to intervene. Kerala’s Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan urged Modi to consider the circumstances of the case, emphasizing its emotional weight: “Considering the fact this is a case deserving sympathy, I appeal to the Hon’ble Prime Minister to take up the matter.”

India’s Minister of State for External Affairs, Kirti Vardhan Singh, assured the parliament that the government prioritizes the welfare of Indians abroad. He stated, “Government of India is providing all possible assistance in the case,” but noted that any resolution involving Priya and the deceased’s family is ultimately a private matter.

The Road to Yemen

Priya first moved to Yemen in 2008, part of a larger trend of individuals from Kerala seeking employment opportunities in the Middle East. She initially worked as a nurse in a local hospital, aspiring to establish her own clinic and create a stable life for her husband, Tomy Thomas, and their young daughter. In 2014, with her husband’s support, she opened her clinic in Sanaa after borrowing funds from family and friends.

The political turmoil in Yemen soon overshadowed her ambitions. In 2015, the situation deteriorated into a full-scale civil war, forcing many expatriates to leave the country. Despite the risks, Priya chose to remain, determined to protect the life and business she had built.

India does not have formal diplomatic relations with the Houthis, which complicates the efforts of those trying to assist Priya. All diplomatic matters are managed through the Indian Embassy in Djibouti, making communication and support particularly challenging for her family.

Yemen has been identified as one of the countries with the highest execution rates, with Amnesty International reporting that the Houthis executed at least one individual in areas under their control in 2024. Those advocating for Priya emphasize the importance of international attention to her case, as it highlights broader human rights issues in the region.

Priya’s mother, a domestic worker from Kerala, has dedicated over a year to securing her daughter’s release, even selling her home to fund legal fees. Meanwhile, Tomy Thomas and their daughter remain hopeful in Kerala, with Thomas expressing unwavering support: “My wife is very good, she is very loving. That is the sole reason I am with her, supporting her and will do so till the end.”

As the clock ticks down to the scheduled execution, the fight to save Nimisha Priya continues, drawing together a network of activists, politicians, and everyday citizens advocating for justice and compassion in a time of crisis.