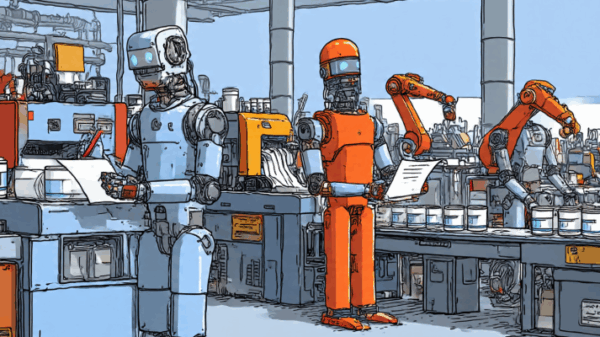

A recent ruling by an administrative law judge has revealed significant issues in a legal document submitted by California State University (CSU), indicating that it contained numerous inaccuracies likely due to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in its preparation. The judge, Bernhard Rohrbacher, ordered the CSU filing to be removed from the record in a case currently under consideration by the California Public Employment Relations Board.

The legal dispute involves the CSU system, the largest public four-year university system in the United States, and the CSU Employees Union, which is seeking to represent approximately 1,400 student resident assistants who help manage housing across the state. The controversial brief, filed on November 10, 2023, included “phantom quotations” from a court decision dating back to 1981. Rohrbacher noted that these misquotes undermined the integrity of CSU’s arguments.

Rohrbacher pointed out that while there is no definitive proof that AI was the author of the brief, it “bears all the hallmarks of the hallucinations associated with AI-generated texts.” The judge found numerous instances of misquoted material that CSU failed to clarify, leading to his decision to strike the brief from the record.

In response to the ruling, CSU issued a statement acknowledging the use of AI in drafting the document. Jason Maymon, a spokesperson for CSU, explained that a staff member had utilized AI without proper diligence, resulting in significant errors that compromised the integrity of their legal work. Maymon emphasized that this practice does not reflect CSU’s ethical standards and that appropriate steps are being taken to address the situation.

The CSU system has been under scrutiny as it navigates the complexities of incorporating AI into its operations. The resident assistants involved in this case provide essential services, such as organizing events and responding to student needs, while receiving benefits like free housing and meal plans, but no salary. The CSU Employees Union has been advocating for the recognition of these students as employees, a move opposed by CSU, which classifies them as “live-in student leaders.”

Catherine Hutchinson, president of the CSU Employees Union, criticized the university for its reliance on AI-generated content, likening it to the standards expected of students. She stated, “If students submit assignments with AI-generated half-truths and fabrications, they face consequences. And yet the CSU is doing exactly what we tell students not to do.” Hutchinson further expressed disappointment at CSU’s efforts to challenge the right of resident assistants to union representation.

As the case unfolds, Rohrbacher highlighted that California law has evolved, noting that the 2018 legislation removed previous definitions that limited certain students’ employee status. His ruling questioned CSU’s interpretation of the legal precedent set in the Marshall case, suggesting it does not support the university’s argument against recognizing resident assistants as employees.

The legal implications of this case extend beyond the immediate dispute. CSU’s approach to AI, as illustrated by this incident, raises questions about the ethical use of technology in academia. Maymon acknowledged that while CSU aims to lead in the adoption of AI in higher education, challenges are inevitable, presenting an opportunity for the institution to refine its training protocols regarding AI for students, faculty, and staff.

As CSU grapples with these revelations, the broader discourse on AI’s role in legal settings and higher education continues to evolve. With ongoing discussions regarding the ethical implications of technology, the CSU case serves as a critical example of the potential pitfalls of integrating AI without adequate oversight.