A recent analysis reveals an unexpected rise in the number of childfree individuals in developing countries, challenging long-held assumptions about parenthood in these regions. Researchers Zachary Neal and Jennifer Neal from Michigan State University presented their findings in the open-access journal PLOS One, highlighting the increasing visibility of childfree populations in areas traditionally associated with high birth rates.

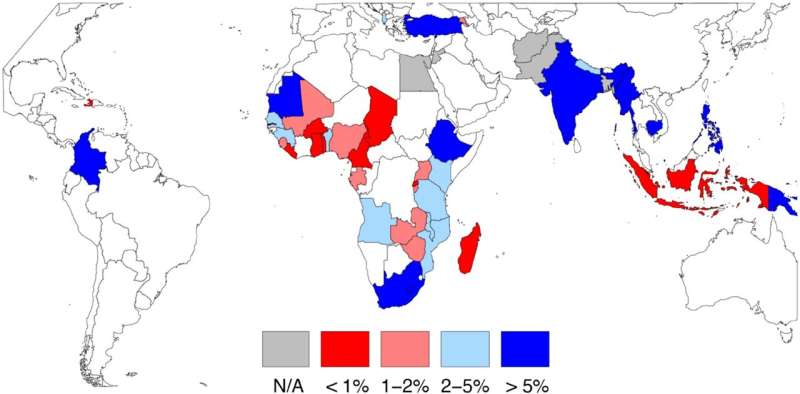

The study focuses on data collected between 2014 and 2023 from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program, which aimed to gather comprehensive fertility statistics. Using innovative analytical software, the researchers examined responses from over 2 million individuals across 51 developing countries, identifying 37,366 who described themselves as childfree—those who have not had children and do not intend to in the future.

Notable Disparities Across Regions

The findings demonstrate significant variation in childfree rates among different countries. For example, in Southeast Asia, approximately 7.3% of single women aged 15 to 29 in the Philippines identified as childfree, while just 0.4% did so in Indonesia. Among the countries analyzed, Papua New Guinea exhibited the highest prevalence at 15.6%, whereas Liberia reported a mere 0.3%.

These discrepancies raise questions about the social and cultural factors influencing reproductive choices, particularly in areas where traditional family structures are prevalent. The researchers noted that understanding these choices could be vital for addressing reproductive health and social service needs in developing regions.

Connections to Development and Gender Equality

Further analysis indicated a correlation between the prevalence of childfree individuals and a country’s Human Development Index (HDI), which measures health, education, and living standards. Countries with lower HDI scores, such as Chad, reported childfree rates near 1%, while those with higher scores, like Turkey, had rates around 6%.

This research also suggests that gender equality and political freedom are linked to childfree prevalence, albeit to a lesser extent. The presence of more equitable social structures appears to facilitate the decision to remain childfree.

The study challenges the notion that the choice to forgo parenthood is confined to wealthier nations. As noted by the authors, “There has been increasing attention to the rising number of individuals in wealthy, highly developed countries who do not want children. However, this research demonstrates that the choice to be childfree is not restricted to the developed world, and that many individuals in developing countries are also choosing not to have children.”

These findings offer critical insights into the evolving landscape of family dynamics in developing countries and highlight the need for a deeper understanding of the reproductive choices individuals make in these contexts. Future research will likely continue to explore the implications of these trends and how they shape societal norms and policies.