Fossilized feces from the ancient settlement known as the Cave of the Dead Children in Durango, Mexico, has provided significant insights into the health of its inhabitants. Research published in the journal PLOS One reveals that these ancient fecal samples, dating back approximately 1,100 to 1,300 years, contain DNA of various intestinal parasites, shedding light on the challenges faced by the Loma San Gabriel people.

The study focused on fecal material found in La Cueva de Los Muertos Chiquitos, which was home to the Loma San Gabriel community between 1,200 and 1,400 years ago. The cave is notable not only for its ancient human remains but also for the preservation of over 500 ancient desiccated fecal samples. Its unique climate, characterized by low humidity, has contributed to the remarkable preservation of these samples since excavations began in the mid-20th century.

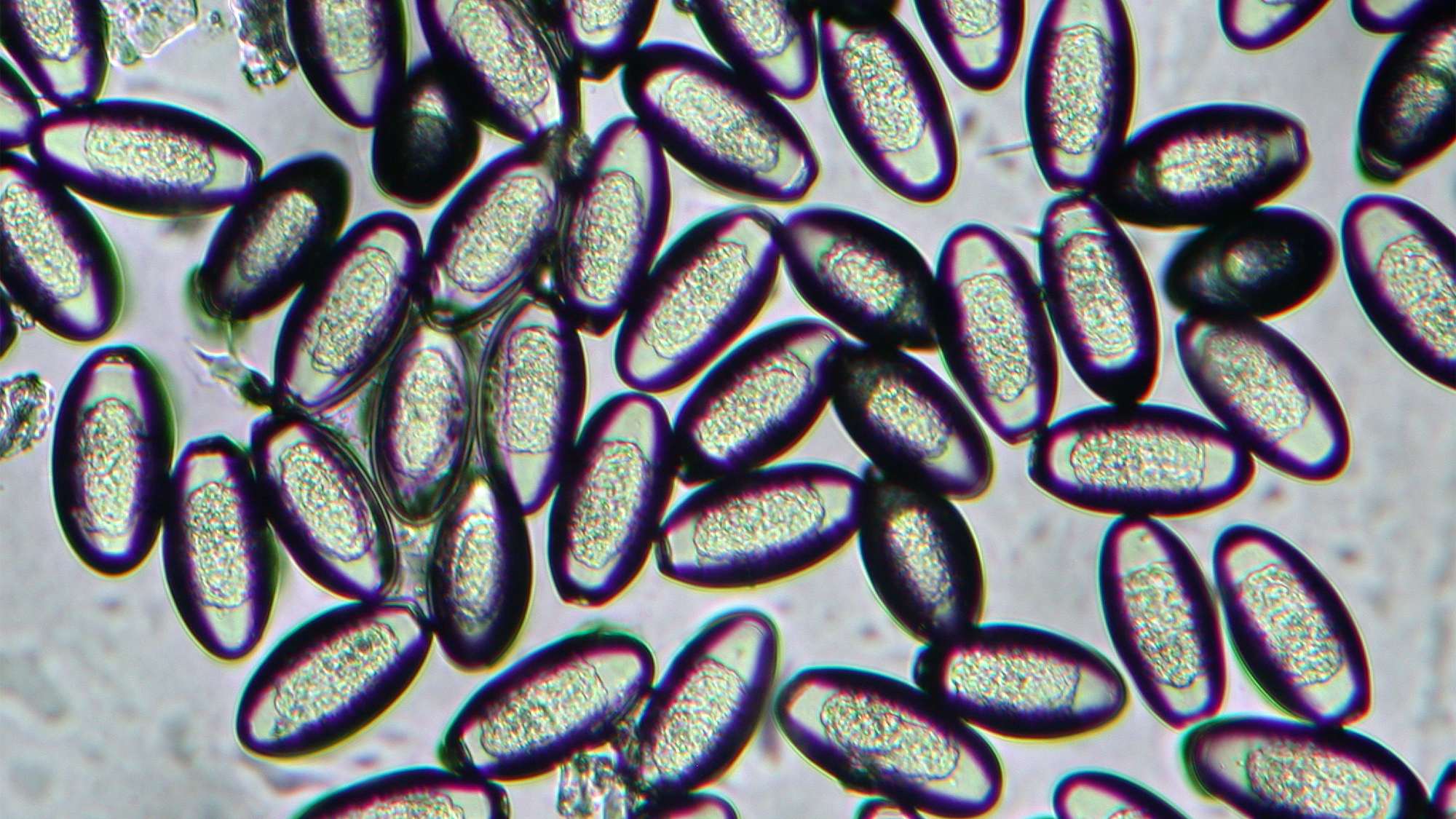

Researchers utilized advanced techniques to analyze the samples, which revealed the presence of various gut parasites, including Shigella and the protozoan Blastocystis. This research marks the first time these specific pathogens have been identified in ancient fecal matter. The findings indicate that intestinal infections, including those caused by pinworm, may have been prevalent in the community.

Joe Brown, a co-author of the study and an environmental engineer at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, emphasized the significance of these findings. “Measuring pathogens in ancient fecal samples is an absolutely fascinating challenge,” he stated. “It can inform our understanding of the health of people living in a very different time and place.”

The study employed a novel approach using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assays, which allowed researchers to identify specific genes associated with enteric pathogens. This method is more targeted than traditional DNA sequencing, which can overlook less concentrated microbes often found in ancient samples.

According to Drew Capone, an environmental health microbiologist at Indiana University and co-author of the study, the prevalence of pinworm DNA in the samples was particularly surprising given the age of the specimens. “When working with modern samples, we are incredibly careful about storing them in ultra-low temperature freezers to minimize degradation before analysis,” Capone explained. “I was incredibly surprised that even after 1,000+ years, DNA from these pathogens had persisted at detectable levels.”

The implications of this research extend beyond historical interest. The identification of human-specific pathogens indicates a need for further study into the health and sanitation conditions of ancient populations. While the current study examined only ten samples, it sets a precedent for using modern molecular methods to explore the health challenges faced by past communities.

Brown noted, “There is a lot of potential in the application of modern molecular methods to inform studies of the past. Highly sensitive and specific targeted assays can complement sequencing approaches when specific targets are of interest.” Future research with larger sample sizes could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the pathogens that affected our ancestors.

The findings from the Cave of the Dead Children not only enrich our understanding of ancient human health but also highlight the lasting impact of intestinal parasites on human populations throughout history. As researchers continue to explore these ancient fecal samples, they hope to uncover further details that could illuminate the lives of those who lived in this region centuries ago.