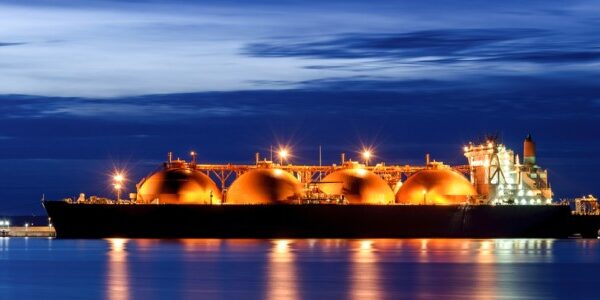

In the event of a conflict between the United States and China, the U.S. Army may play a crucial role through its advanced missile capabilities. While the Army is not expected to engage in a ground invasion of major cities such as Shanghai, its arsenal includes long-range munitions capable of striking targets on the Chinese mainland. This includes systems like the Precision Strike Missile, the Typhon Strategic Mid-Range Fires system, and the Dark Eagle Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon, which can reach distances of up to 3,000 kilometers. Among the potential targets are Chinese ports that serve as vital nodes for the Chinese military and economy.

Capt. Micah Neidorfler, in an essay for Military Review, presents a controversial perspective on targeting these strategic infrastructures. He argues that rather than destroying Chinese ports, the U.S. Army should aim to preserve them for post-conflict use. This notion challenges longstanding military doctrine that advocates for crippling an enemy’s infrastructure to compel capitulation. Neidorfler points out that despite efforts to reduce economic dependence on China, the U.S. economy remains significantly intertwined with China’s, relying on imports for essential goods and providing a market for American exports.

Neidorfler highlights the importance of maintaining operational capabilities for Chinese ports even during a conflict. He notes, “U.S. joint doctrine specifically identifies ports as targets, and predictions for a U.S.-China war perceive Chinese ports as likely targets for U.S. strikes.” However, he warns that severely damaging these ports could have detrimental effects on the global economy, potentially leading to a pyrrhic victory for the United States. With an unconditional surrender from China unlikely, any resolution would require a negotiated peace, necessitating the restoration of trade relations with China.

The complexity of port operations offers a potential solution. Neidorfler emphasizes that ports are composed of numerous vulnerable components, including cranes, rail yards, and storage facilities. By targeting these specific elements, the Army could disrupt port operations without inflicting long-term damage, allowing for a quicker return to normalcy post-conflict. This strategy would not only achieve immediate military objectives but also mitigate the risks of escalating tensions further.

The broader implications of this strategy raise questions about the Army’s evolving role in a potential Pacific conflict. Neidorfler notes that analyses of a possible U.S.-China war often overlook the Army’s contributions. Over the past decade, the Army has focused on enhancing command and control, sustaining joint forces, and providing air defense capabilities.

Debates over whether the U.S. would actually strike Chinese ports are complicated by China’s military capabilities, including its significant nuclear arsenal. Lonnie Henley, a researcher at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, cautions against assuming that an aggressive military stance is guaranteed. He notes, “Who knows what some future president in some unspecified global circumstances would decide.” Henley also points out logistical challenges; launching long-range missiles requires a solid operational base and sustained support, which could be difficult to establish.

In addition, the U.S. Air Force and Navy already possess substantial missile capabilities. Henley questions the added value of the Army’s contributions in this regard, suggesting that the U.S. and its allies could effectively block most of China’s maritime trade without directly targeting ports. He adds, “What’s the added benefit of seizing ports in third countries? None that I can see.”

Despite potential pushback against Neidorfler’s suggestions, he argues for a strategy that involves the Army potentially seizing Chinese-owned ports in other nations. Given China’s extensive investments in overseas port infrastructure—estimated at 129 projects globally—this approach could provide leverage in negotiations or prevent ports from being used as military bases.

However, Neidorfler acknowledges the political complexities involved. Seizing foreign assets raises significant sovereignty issues for host nations, and unilateral action by the U.S. military is unlikely to be welcome. He suggests that collaboration with third-party nations may be a more realistic approach, especially given the reluctance of many countries, particularly in the Global South, to support U.S. military interventions.

As the discussion unfolds, experts on U.S.-China relations remain skeptical of these military strategies. The necessity of a well-thought-out approach is evident. Neidorfler concludes that, in the absence of a nuclear confrontation, any war between the U.S. and China would inevitably lead to a peace agreement that must be acceptable to both sides. For the Army to effectively prepare for a conventional war, it must recognize that long-term stability hinges on a mutually beneficial resolution.